History has shown that as markets rise and fall, people’s choices in an economy are vulnerable to frenzies and panics. During an economic boom, people have more money, so they want to buy more goods, causing the prices of goods to rise, which fuels demands for higher wages, which means people have even more money.

This is an inflationary spiral, and it happened to Germany in the 1920s, Brazil in the 1980s, and Argentina in the 1990s. Similarly, in an economic bust, people are afraid to buy goods, causing the prices of goods to drop, driving people to put off purchases further until prices fall even more, and so on.

This is known as a deflationary spiral—and it almost occurred during the global recession of 2008.

In both of these situations, a responsible central bank can step in to cut off these destructive feedback loops.

But how do central banks manage this task?

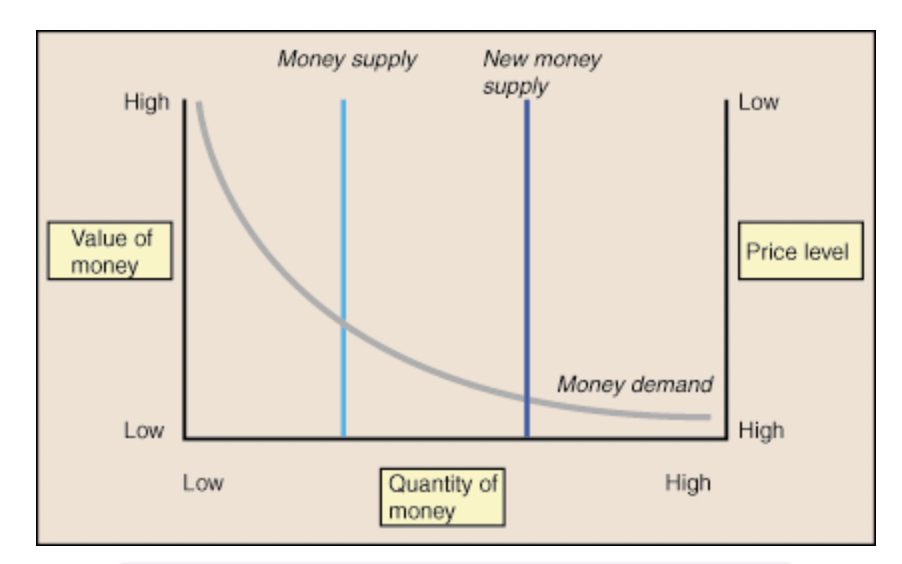

Imagine that prices in an economy are at some level—say, the average cost of a predefined “basket of goods” is $100. The Quantity Theory of Money says that if you doubled the amount of money that everyone had in their bank accounts, then, in the long run, that same basket of goods would cost $200. Why? While the nominal amount of money for everyone has doubled, the true value of goods has stayed the same. This means that people should be willing to part with twice as much nominal money to get the same amount of value. The same principle applies in the reverse: If we yanked half of the peoples’ savings out of the economy, then, in the long run, our same basket of goods would cost only $50.

Extending this concept, we consider the case of a central bank trying to calm inflation. High prices that are constantly rising mean that people are too willing to spend money.

To restore prices, we could restrict people to have less money. (Let’s put aside how for now.) Similarly, the opposite applies to deflation, which makes people unwilling to spend money. To restore prices, we could give people more money. This simple but important idea is exactly what central banks do to stabilize prices. While the tools

that central banks use to implement monetary policy can be abstruse and difficult to understand, e.g., open market operations and reserve requirements, a central bank does two things at a high level:

• Expand the money supply. If a central bank sees that prices are going down,

it can expand the money supply to bring them back up.

• Contract the money supply. If a central bank sees that prices are going up,

it can contract the money supply to bring them back down.

Expanding and contracting the money supply works because the Quantity Theory of Money states that long-run prices in an economy are proportional to the total supply of money in circulation. Below is an example of the theory, applied to keep price levels

Stable in a currency like Ant Token:

• Suppose you want to peg a currency like Ant Token such that 1 token always trades for 1 USD. We’ll show that you can do this by growing or shrinking the supply of tokens in proportion to how far the current exchange rate is from the desired peg.

• First, we introduce the concept of aggregate demand. Conceptually, aggregate demand describes how much people in aggregate want the coin:

demand = (coin price) * (number of coins in circulation)

This is also known as a coin’s market cap, since market cap equivalently describes how many people in aggregate value the coin.

• Let X represent the number of coins in circulation, i.e., coin supply. Suppose that demand has risen over the past few months such that coins are now trading for $1.10:

demand = $1.10 * X

• To determine how coin supply can be adjusted to restore the peg of $1, assume that demand stays constant, and let Y represent the desired number of coins in circulation:

demand_before = $1.10 * X

demand_after = $1.00 * Y

demand_before = demand_after

• Solving for Y implies that in order to get your coin to trade at $1, you need to increase the supply of your coin by a factor of 1.1:

Y = X * 1.1

As a rough estimate, the Quantity Theory of Money finds that if the Ant Token is trading at some price P that is too high or too low, the protocol can restore long-term prices to $1 by multiplying existing supply by P.

There are some technical details that we’ll get to later about how fast the protocol must respond, how fast prices will respond, and so on—but the core idea is that to maintain a peg in the long term, we just need

to measure the price of the Ant Token and adjust the Ant Token supply accordingly.

Monetarists in the 1980s thought that, by targeting money supply growth, the level of goods and service prices in an economy could be controlled. However, although there is a link between the general level of prices in an economy and the amount of money, it is not rigid, and prices can move up and down for a myriad of reasons.

Nevertheless, the general relationship in the Quantity Theory of Money stands. More money in an economy (inflation) tends to lead to higher prices and less money (deflation) tends to lead to lower prices.

The Ant Token instead of being pegged to $1, has its value increase to 10% per year. Therefore the target asset isn’t the US Dollar but we use the USD only as starting point. Our Target is a constant 10% increase per year from the genesis ant token value, which will be at the time of creation $1.

This article is taken from the Basis White Paper.